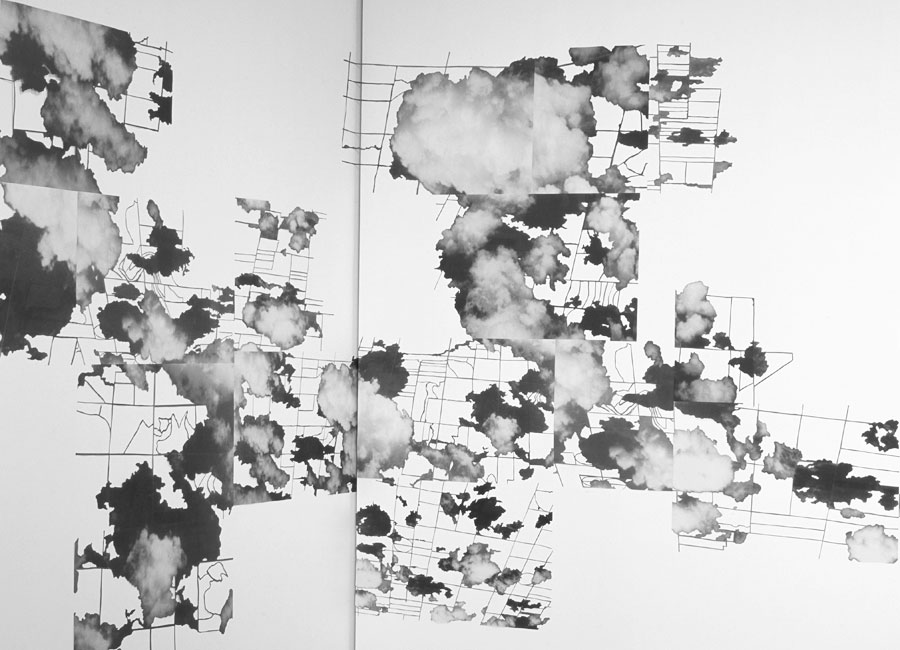

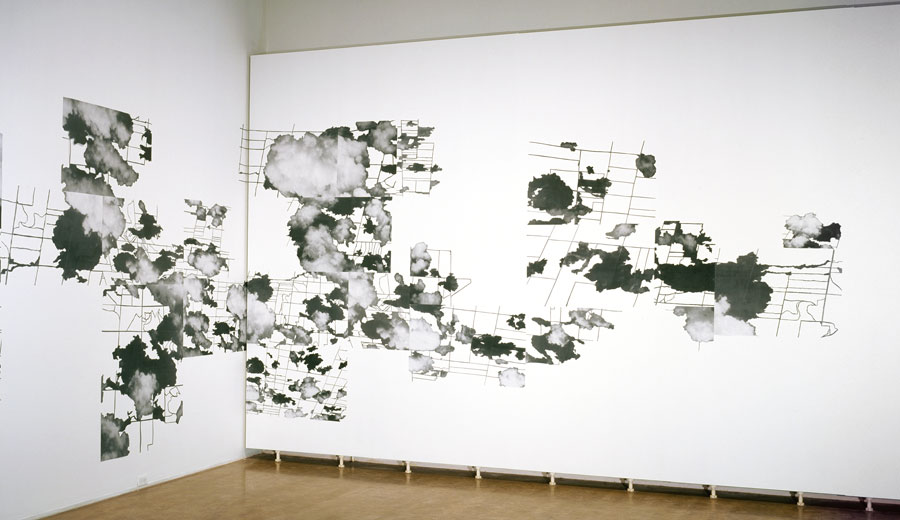

Cloudgrids 3 (2002) Cut-out b/w silkscreen prints on paper.

Individual images approx. 90cm x 60cm. Total area approx: 15m x 3.5m.

Cloudgrids 3 Detail

Cloudgrids 3 Detail

CUT LAND/TERRE TRANCHÉE

Centre VU (solo exhibition & residency), Quebec, Canada (2002)

Some people need a drink when they’re flying (they can’t bear the feeling of their bodies floating above water or cities). Others, like Annabel Howland, take pictures. From the skies above she gleans what she can with her camera: clouds, fields that lie fallow, deserts and motorways.

For those of us who remain on the ground, the landscape is not as spectacular. When travelling by car, folding the map properly may be the least boring part of the journey. The landscape that rushes past us seems

insipid. The recurrence of cracks in the asphalt, of fields, pylons and fir trees creates a monotonous rhythm. In the background, houses, gas stations and restaurants follow the same pattern. If the journey seems interminable, you can isolate and frame a part of the landscape in which you can then mentally project yourself. You may feel that this appropriation singles out this section of landscape, but in reality, it is a sample of a familiar geography that

differs very little from any other.

We find such landscapes in the photographic installations of Annabel Howland. However, they have acquired a singularity in the way their quality shifts from that of an object to that of an image. The images used by Howland are aerial photographs that have been cut up into a fragile network of lines. Only the roads, the outlines of fields and the clouds remain intact. The portions of land in between these elements have been removed from the photographs. With skill and a sense of economy, Howland constructs from these photographic residues an ethereal diorama which spreads across the walls of the gallery. In Cloudgrids (2001-2), the alternation and recurrence of images of clouds and their shadows creates a lateral movement that pushes the clouds along the wall, as if they had been dispersed by wind. The same images are used at different scales, sometimes repeated, sometimes inverted. The artist stabilises the precariousness of this assemblage by insisting on the irregularity of the outlines through a very precise cutting of this outline. By remaining intact and whole, the exterior edge of the photograph also emphasises the construction of the work. The links between the different images are interrupted by jolts, syncopations and undecipherable moments, not unlike an old film that suddenly blocks or accelerates for a moment to eventually bring us back to where we were. We are reminded of when we were children and discovered that a film is actually made of sequence shots filmed randomly and then edited to create a narrative continuity. The shock of this discovery eventually brings us closer to film and makes us understand all the invisible actions and decisions the author had to make for the work to exist.

Howland’s photographic installations are also very similar to drawing. The repeated motifs, their regular arrangement evokes a glide-reflection system used to draw plans of architectural friezes. Juxtapositions,

annexations, intersections and liaisons between the objects that have been photographed and cut up alter their image in a way that refers to drawing differently, by creating an almost abstract image that evokes the exalted lines of a nervous drawing. But Howland doesn’t disfigure the original image in any way. Her intervention in the photographs is a positive action despite the fact that it is done by taking away parts of the image. The photograph is stripped of any critical moment, but reveals traces of many moments. Howland accentuates the existing configurations of the landscape by cutting around them. She underlines them as would someone reading a book, literally underlining passages that are important, incomprehensible or simply moving.

What has been disfigured here is not the appearance of a bucolic landscape, but rather the autonomy and quality of wholeness we tend to attribute to images in landscape photography. The photographic fragments of Cloudgrids suggest a vast background, a spatial depth, an action that that continues beyond their edges. Annabel Howland’s work keeps us at a distance from these images, but it is not a great distance; we seem to be just above them, able to go where we would normally not be able to. This spatial experience enables us to fly above our own trajectory without fear, without boredom, and with no maps to fold.

Mireille Lavoie, Montreal/Quebec City, 2002